Major Joseph Gray in 1940.

Gray’s first years in London (1931-33) proved promising. He rented a studio at 33 Tite Street in Chelsea (the same rooms that had previously been occupied by John Singer Sargent). There he painted scenes of the Thames alongside focusing on portraiture.

In 1933 he was commissioned by Lord Brocket to paint a full-length portrait, but Brocket died before any payment was made. This virtually ruined Gray. He gave up his studio and could find no further means of income.

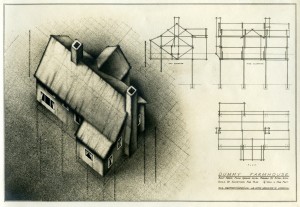

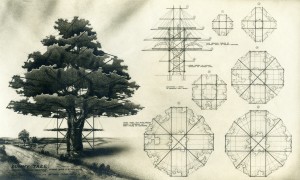

Drawings for the steel wool camouflage construction of a dummy tree and farmhouse.

As the years passed Gray became increasingly certain there would be another war. His prospects as an artist were shrinking. Although aware that he would be too old to return to the firing line, he began to consider other ways where his experience and skills might be put to use.

The constructions were made by

M&E Equipment Ltd under Gray’s instruction.

Gray became interested in camouflage, specifically how Britain’s cities might be protected from the growing threat of German air attack.

He visited the Imperial War Museum, using his contacts there to gain access to the extensive archive of German, French and English camouflage materials. Thus he began a comprehensive study of large-scale static camouflage.

Major Joseph Gray standing in a bomb store concealed beneath a steel wool cover c1941.

Joseph Gray atop a steel wool camouflage cover.

Many artists would be recruited into the war effort soon enough, channelling their creative talents into camouflage, but Gray was one of the first. As early as 1936 he had completed his treatise, Camouflage and Air Defence, which he submitted to the War Office. He was soon recruited into the Royal Engineers and was sent all around the country visiting sites of national importance, working out ways to hide them.

Cecil Schofield, partner in the firm M&E Equipment, beneath Gray’s first steel wool camouflage cover at Cobham

in the winter of 1940.

During the early years of the war he also devised a kind of steel wool camouflage which was used to conceal large military bases and factories from air attack. (For this material he would later be granted an ex-gratia award).

Steel wool camouflage construction c1941.

Gray’s notes from his time as a camouflage officer and his research and experiments into steel wool are now kept in the Imperial War Museum Archive. There are photographs, drawings, samples of material, reports and memoranda. (IWM Archive Major J. Gray 83/38/1.)

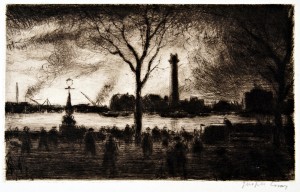

To his co-workers he was known as ‘Uncle Grumble,’ and he became infamous for his nightly rambles through the blitzed London streets, ignoring air raid warnings, witnessing scenes which he would later immortalise in the Battle of Britain etchings series.

‘The First Blitz.’

‘Blitz, Dawn.’

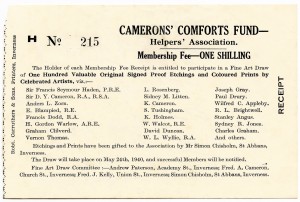

The Fine Art Draw raffle ticket

which took place in May 1940.

Joseph Gray, Mary Meade and fellow camoufleur John Churchill, nephew of prime-minister Winston Churchill, sitting on the steps of 6 Landsdown Crescent, Bath, c1942.

During this time Gray’s works still helped raise money for regimental charities, in particular the Fine Art Draw of May 1940, where 100 valuable original signed etchings and prints by celebrated artists were raffled for Andrew Paterson’s Camerons’ Comforts Fund.

Gray at York aerodrome, July 1941.

(Pic: Tom Van Oss)

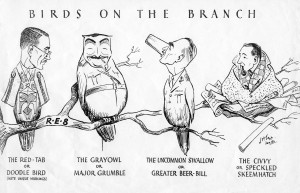

A cartoon of the men of R.E.S.B. by one of

their number, Jack Sayer, featuring the

Gray Owl, Major Grumble.

The Imperial War Museum holds many documents relating to Joseph Gray.

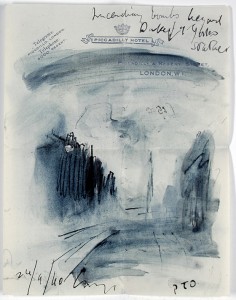

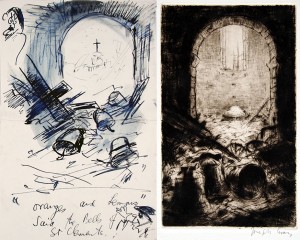

Sketch of incendiary bombs on

London, September 1940, drawn on Piccadilly Hotel stationery.

Preliminary sketch of bomb damage at St.Clements Danes Church on the Strand, with a cartoon of Hitler looking down at a defiant Tommy, and the finished etching, ‘The Bells of St.Clements.’

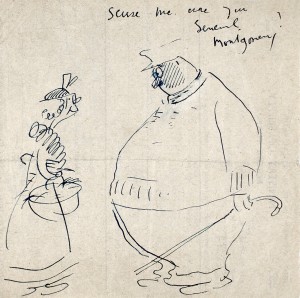

“Scuse me, are you General Montgomery?” —

an unofficial self-portrait.

For more on the Camerons’ Comforts Fund visit our sister site

For more on the Camerons’ Comforts Fund visit our sister site.